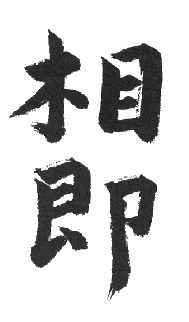

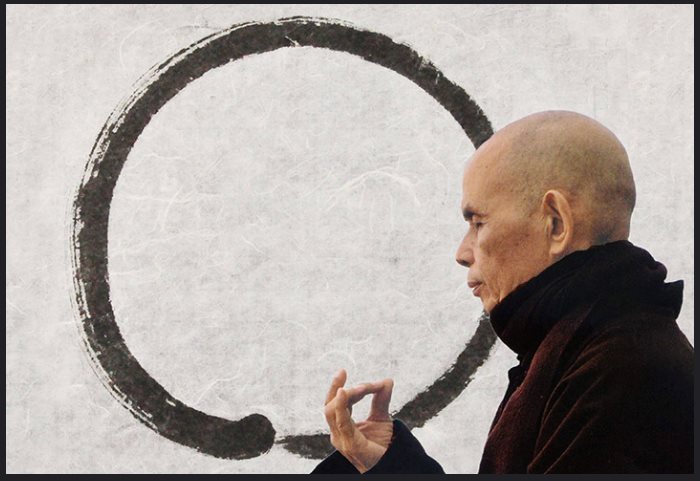

by Pam Marraccini | afflictions, awareness, breathing, Buddha, compassion, consciouness, deep listening, enlightenment, freedom, garden, heart, jewel, meditation, mindfulness, Peace, seeds, Thich Nhat Hanh

An excerpt: Beginning Anew, Ceremony for the Deceased,

Chanting From the Heart, Buddhist Ceremonies and Daily Practices

by Thich Nhat Hanh and the Monks and Nuns of Plum Village

…With all our heart we go for refuge.

Turning to the Buddhas in the 10 directions

and all the Bodhisattvas, noble disciples, and self-achieved Buddhas

very sincerely we recognize our errors

and the mistakes of our wrong judgements.

Please bring the balm of clear water

to pour on the roots of our afflictions.

Please bring the raft of the true teachings

to carry us over the ocean of sorrows.

We vow to live an awakened life,

to practice smiling and conscious breathing

and to study the teachings, authentically transmitted.

Diligently, we shall live in mindfulness.

We come back to live in the wonderful present,

to plant our heart’s garden with good seeds,

and to make strong foundations of understanding and love.

We vow to train ourselves in mindfulness and concentration,

practicing to look and understand deeply

to be able to see the nature of all that is,

and so to be free of the bonds of birth and death.

We learn to speak lovingly, to be affectionate,

to care for others whether it is early morn or late afternoon,

to bring the roots of joy to many places,

helping people to abandon sorrow,

to respond with deep gratitude

to the kindness of parents, teachers, and friends.

With deep faith, we light up the incense of our heart.

We ask the Lord of Compassion to be our protector

On the wonderful path of practice.

We vow to practice diligently,

cultivating the fruits of this path.

by Pam Marraccini | afflictions, anger, awareness, breathing, compassion, consciouness, deep listening, equanimity, garden, happiness, heart, joy, listening, love, meditation, mindfulness, Peace, present, true home, understanding

Heart Like a R iver, Page 8

iver, Page 8

If you pour a handful of salt into a cup of water, the water becomes undrinkable. But if you pour the salt into a river, people can continue to draw the water to cook, wash, and drink. The river is immense, and it has the capacity to receive, embrace, and transform. When our hearts are small, our understanding and compassion are limited, and we suffer. We can’t accept or tolerate others and their shortcomings, and we demand that they change. But when our hearts expand, these same things don’t make us suffer anymore. We have a lot of understanding and compassion and can embrace others. We accept others as they are, and then they have a chance to transform. So the big question is: how do we help our hearts to grow?

Feeding our Love, Page 9

Each of us can learn the art of nourishing happiness and love. Everything needs food to live, even love. If we don’t know how to nourish our love, it withers. When we feed and support our own happiness, we are nourishing our ability to love. That’s why to love means to learn the art of nourishing our happiness.

Love is Organic, Page 14

Love is a living, breathing thing. There is no need to force it to grow in a particular direction. If we start by being easy and gentle with ourselves, we will find it is just there inside of us, solid and healing.

Be Beautiful, Be Yourself, Page 23

If you can accept your body, then you have a chance to see your body as your home. You can rest in your body, settle in, relax, and feel joy and ease. If you don’t accept your body and your mind, you can’t be at home with yourself. You n=have to accept yourself as you are. This is a very important practice. As you practice building a home in yourself, you become more and more beautiful.

The Practice of Metta, Page 64

To love is, first of all, to accept ourselves as we actually are. The first practice of love is to know oneself. The Pali word Metta means “loving kindness.” When we practice Metta Meditation, we see the conditions that have caused us to be the way we are; this makes it easy to accept ourselves, including our suffering and happiness. When we practice Metta Meditation, we touch our deepest aspirations. But the willingness ad aspiration to love is not yet love. We have to look deeply, with all our being, in order to understand the object of our meditation. The practice of love meditation is not autosuggestion. We have to look deeply at our body, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. We can observe how much peace, happiness, and lightness we already have. We can notice whether we are anxious about accidents or misfortunes, and how much anger, irritation, fear, anxiety or worry are still in us. As we become aware of the feelings in us, our self-understanding will deepen. We will see how our fears and lack of peace contribute to our unhappiness, and we will see the value of loving ourselves and cultivating a heart of compassion. Love will enter our thoughts, words, and actions.

by Pam Marraccini | afflictions, anger, awareness, Buddha, ignorance, mental formation, mind consciousness, understanding

In Buddhist psychology, the word samyojana refers to internal formations, fetters or knots. When someone says something unkind to us, for example, if we do not understand why he said it and we become irritated, a knot will be tied in us. The lack of understanding is the basis for every internal knot. It is difficult for our mind to accept that it has negative feelings like anger, fear, and regret, so it finds ways to bury these in remote areas of our consciousness. We create elaborate defense mechanisms to deny their existence, but these problematic feelings are always trying to surface. If we practice mindfulness, we can learn the skill of recognizing a knot the moment it is tied in us, so that the work of untying them will be easy. Otherwise, they will grow tighter and stronger.

In Buddhist psychology, the word samyojana refers to internal formations, fetters or knots. When someone says something unkind to us, for example, if we do not understand why he said it and we become irritated, a knot will be tied in us. The lack of understanding is the basis for every internal knot. It is difficult for our mind to accept that it has negative feelings like anger, fear, and regret, so it finds ways to bury these in remote areas of our consciousness. We create elaborate defense mechanisms to deny their existence, but these problematic feelings are always trying to surface. If we practice mindfulness, we can learn the skill of recognizing a knot the moment it is tied in us, so that the work of untying them will be easy. Otherwise, they will grow tighter and stronger.

by Pam Marraccini | afflictions, anger, awareness, breathing, compassion, deep listening, energy, happiness, heart, joy, love, mental formation, mindfulness, nonduality, present, seed, suffering, Thich Nhat Hanh, Uncategorized, understanding

A Sutra on the Full Awareness of Breathing

By Thich Nhat Hanh

Subject Five: Observing Our Feelings

- Breathing in, I am aware of my mental formations.

Breathing out, I am aware of my mental formations.

- Breathing in, I calm my mental formations.

Breathing out, I calm my mental formations.

Mental formations are psychological phenomena. There are fifty-one mental formations according to the Vijnanavada School of the Mahayana, and fifty-two according to the Theravada. Feelings are one of them. In the seventh and eighth breathing exercises, mental formations simply mean feelings. They do not refer to the other fifty mental formations. In the Vimutti Magga, we are told that mental formations in these exercises mean feelings and perceptions. It is more likely that mental formations here simply mean feelings, although feelings are caused by our perceptions.

Some feelings are more rooted in the body, such as a toothache or a headache. Feelings that are rooted in our mind arise from our perceptions. In the early morning when you see the first light of day and hear the birds singing, you might have a very pleasant feeling. But if once at this time of day you received a long distance telephone call that your parent had suffered a heart attack, the feeling that comes from that perception may be painful for many years.

When you feel sad, do you remember that it will not last forever? If someone comes and smiles at you, your sadness may vanish right away. In fact, it has not gone anywhere. It has just ceased to manifest. Two days later, if someone criticizes you, sadness may reappear. Whether the seed of sadness is manifesting or not depends on causes and conditions. Our practice is to be aware of the feeling that is present right now. “Breathing in, I am aware of the feeling that is in me now. Breathing out, I am aware of the feeling that is in me now.”

If it is a pleasant feeling, when we are aware that it is a pleasant feeling, it may become even more pleasant. If we are eating or drinking something that is healthy and nourishing for us, our feeling of happiness will grow as we become aware of it. If what we are consuming is harmful for our intestines, our lungs, our liver, or our environment, our awareness will reveal to us that our so-called pleasant feeling has within it many seeds of suffering.

The seventh and eighth breathing exercises help us observe all our feelings – pleasant and unpleasant, neutral and mixed. Feelings, arising from irritations, anger, anxiety, weariness, and boredom, are disagreeable ones. Whatever feeling is present, we identify it, recognize that it is there, and shine the sun of our awareness on it.

If we have an unpleasant feeling, we take that feeling in our arms like a mother holding her crying baby. The “mother” is mindfulness and the “crying baby” is the unpleasant feeling. Mindfulness and conscious breathing are able to calm the feeling. If we do not hold the unpleasant feeling in our arms but allow it just to remain in us, it will continue to make us suffer. “Breathing in, I touch the unpleasant feeling in me. Breathing out, I touch the unpleasant feeling in me.”

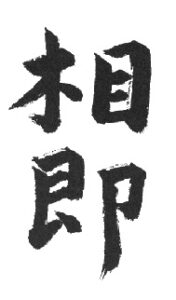

In Buddhist meditation, looking deeply is based on non-duality. Therefore, we do not view irritation as an enemy coming to invade us. We see that we are that irritation in the present moment. When we are irritated we know, “This irritation is in me. I am this irritation,” and we breathe in and out in this awareness. Thanks to this approach, we no longer need to oppose, expel, or destroy our irritation. When we practice looking deeply, we do not set up barriers between good and bad in ourselves and transform ourselves into a battlefield. We treat our irritations with compassion and nonviolence, facing it with our heart filled with love, as if we were facing our own baby sister. We bring the light of awareness to it by breathing in and out mindfully. Under the light of awareness, our irritation is gradually transformed. Every feeling is a field of energy. A pleasant feeling is an energy that can nourish. Irritation is a feeling that can destroy. Under the light of awareness, the energy of irritation is transformed into a kind of energy that nourishes us.

Feelings originate either in the body or in your perceptions. When we suffer from insomnia, we feel fatigue or irritation. That feeling originates in our body. When we misperceive a person or an object, we may feel anger, disappointment, or irritation. This feeling originates in our perception. According to Buddhism, our perceptions are often inaccurate and cause us to suffer. The practice of Full Awareness is to look deeply in order to see the true nature of everything and to go beyond our inaccurate perceptions. Seeing a rope as a snake, we may cry out in fear. Fear is a feeling, and mistaking the rope for a snake is an inaccurate perception.

If we live our lives in moderation, keeping our bodies in good health, we can diminish painful feelings which originate in the body. By observing each thing clearly and opening the boundaries of our understanding, we can diminish painful feelings that originate from perceptions. When we observe a feeling deeply, we recognize the multitude of causes near and far that helped bring it about, and we discover the very nature of feeling.

When a feeling of irritation or fear is present, we can be aware of it, nourishing our awareness through breathing. With patience, we come to see more deeply into the true nature of this feeling, and in seeing, we come to understand, and understanding brings us freedom. The seventh exercise refers to the awareness of a mental formation, namely a feeling. When we have identified the feeling, we can see how it arises, exists for a while, and ceases to be in order to become something else.

With mindfulness, a so-called neutral feeling can become a pleasant or an unpleasant feeling. It depends on your way of handling it. Suppose you are sitting in the garden with your little boy. You feel wonderful. The sky is blue, the grass is green, there are many flowers, and you are able to touch the beauty of nature. You are very happy, but your little boy is not. First, he has only a neutral feeling but, since he doesn’t know how to handle it, it turns into boredom. In his search for more exciting feelings, he wants to run into the living room and turn on the television. Sitting with the flowers, the grass, and the blue sky is not fun for him. The neutral feeling has become an unpleasant feeling.

Mindfulness helps us to identify a feeling as a feeling and an emotion as an emotion. It helps us hold our emotions tenderly within us, embrace them, and look deeply at them. By observing the true nature of any feeling, we can transform it’s energy into the energy of peace and joy. When we understand someone, we can accept and love him. The energy of the feeling of irritation, in this case, has been transformed into the energy of love. The Buddha had much love and compassion as far as the body and feelings of people are concerned. He wanted his disciples to return to, look after, care for, heal, and nourish their bodies and minds. How deeply the Buddha understood human beings!

by Pam Marraccini | afflictions, anger, breathing, Buddhist psychology, compassion, concentration, energy, inner child, meditation, mental formation, mind consciousness, mindfulness, nonduality, seed, store consciousness, Thich Nhat Hanh, walking meditation

by Thich Nhat Hanh

CHAPTER ONE

The Energy of Mindfulness

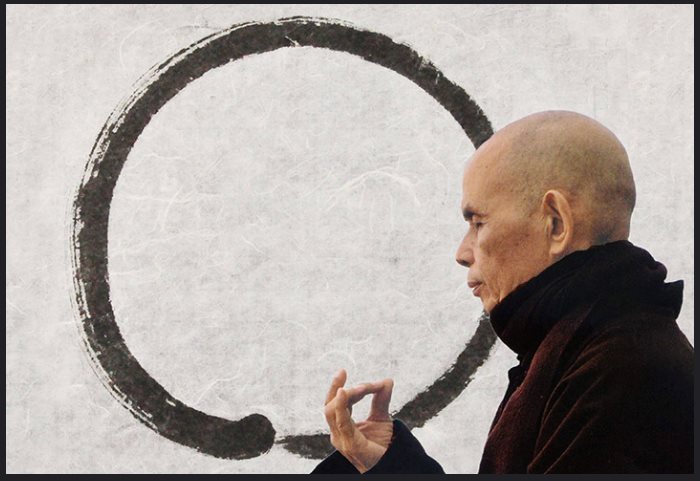

The energy of mindfulness is the salve that will recognize and heal the child within. But how do we cultivate this energy?

Buddhist psychology divides consciousness into two parts. One part is mind consciousness and the other is store consciousness. Mind consciousness is our active awareness. Western psychology calls it “the conscious mind.” To cultivate the energy of mindfulness, we try to engage our active awareness in all our activities and be truly present with whatever we are doing. We want to be mindful as we drink our tea or drive through the city. When we walk, we want to be aware that we are walking. When we breathe, we want to be aware that we are breathing.

Store consciousness, also called root consciousness, is the base of our consciousness. In Western psychology it’s called “the unconscious mind.” It’s where all our past experiences are stored. Store consciousness has the capacity to learn and to process information.

Often our mind is not there with our body. Sometimes we go through daily activities without mind consciousness being involved at all. We can do many things by means of store consciousness alone, and mind consciousness can be thinking of a thousand other things. For example, when we drive our car through the city, mind consciousness may not be thinking about driving at all, but we still reach our destination without getting lost or having an accident. That is our store consciousness operating on its own.

Consciousness is like a house in which the basement is our store consciousness and the living room is our mind consciousness. Mental formations like anger, sorrow, or joy rest in the store consciousness in the form of seeds (bija). We have a seed of anger, despair, discrimination, fear, a seed of mindfulness, compassion, a seed of understanding, and so on. Store consciousness is made of the totality of the seeds, and it is also the soil that preserves and maintains all the seeds. The seeds stay there until we hear, see, read, or think of something that touches a seed and makes us feel the anger, joy, or sorrow. This is a seed coming up and manifesting on the level of mind consciousness, in our living room. Now we no longer call it a seed, but a mental formation.

When someone touches the seed of anger by saying something or doing something that upsets us, that seed of anger will come up and manifest in mind consciousness as the mental formation (cittasamskara) of anger. The word “formation” is a Buddhist term for something that’s created by many conditions coming together. A marker pen is a formation; my hand, a flower, a table, a house, are all formations. A house is a physical formation. My hand is a physiological formation. My anger is a mental formation. In Buddhist psychology we speak about fifty-one varieties of seeds that can manifest as fifty-one mental formations. Anger is just one of them. In store consciousness, anger is called a seed. In mind consciousness, it’s called a mental formation.

Whenever a seed, say the seed of anger, comes up into our living room and manifests as a mental formation, the first thing we can do is to touch the seed of mindfulness and invite it to come up too. Now we have two mental formations in the living room. This is mindfulness of anger. Mindfulness is always mindfulness of something. When we breathe mindfully, that is mindfulness of breathing. When we walk mindfully, that is mindfulness of walking. When we eat mindfully, that is mindfulness of eating. So in this case, mindfulness is mindfulness of anger. Mindfulness recognizes and embraces anger.

Our practice is based on the insight of nonduality – anger is not an enemy. Both mindfulness and anger are ourselves. Mindfulness is not there to suppress or fight against anger, but to recognize and take care. It’s like a big brother helping a younger brother. So the energy of anger is recognized and embraced tenderly by the energy of mindfulness.

Every time we need the energy of mindfulness, we just touch that seed with our mindful breathing, our mindful walking, smiling, and then we have the energy ready to do the work of recognizing, embracing, and later on looking deeply and transforming. Whatever we’re doing, whether its cooking, sweeping, washing, walking, being aware of breathing, we can continue to generate the energy of mindfulness, and the seed of mindfulness in us will become strong. Within the seed of mindfulness is the seed of concentration. With these two energies, we can liberate ourselves from afflictions.